PYRAMID x SCQA

Thinking Principles

I. Pyramid

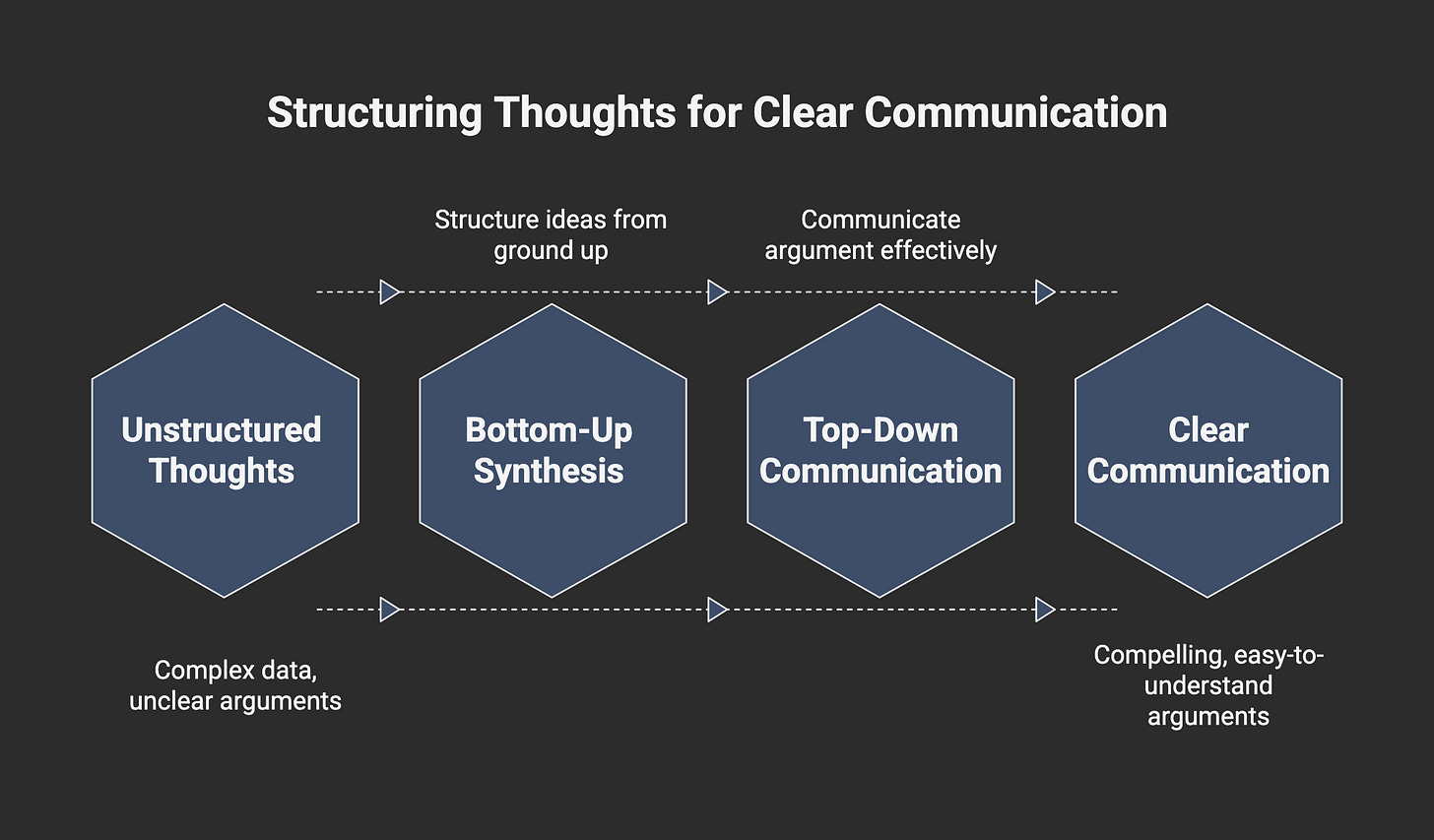

In environments saturated with information, mastering the art of structuring and communicating thoughts is not just a valuable skill but a critical advantage. The Pyramid Principle, developed by Barbara Minto at McKinsey, is a powerful tool that can empower you to transform complex data into compelling, easy-to-understand arguments. This method, revered in consulting and business, can be best understood in two fundamental parts: first, the bottom-up process of synthesis and sensemaking, and second, the top-down method of communication.

Building the Pyramid: Bottom-Up Synthesis and Sensemaking

The foundation of clear communication lies in rigorous thinking. The first part of the Pyramid Principle guides you through structuring your ideas from the ground up, turning raw data into a cohesive argument. Following this method can lead to a sense of accomplishment as you see your ideas come to life.

The Structure of the Pyramid

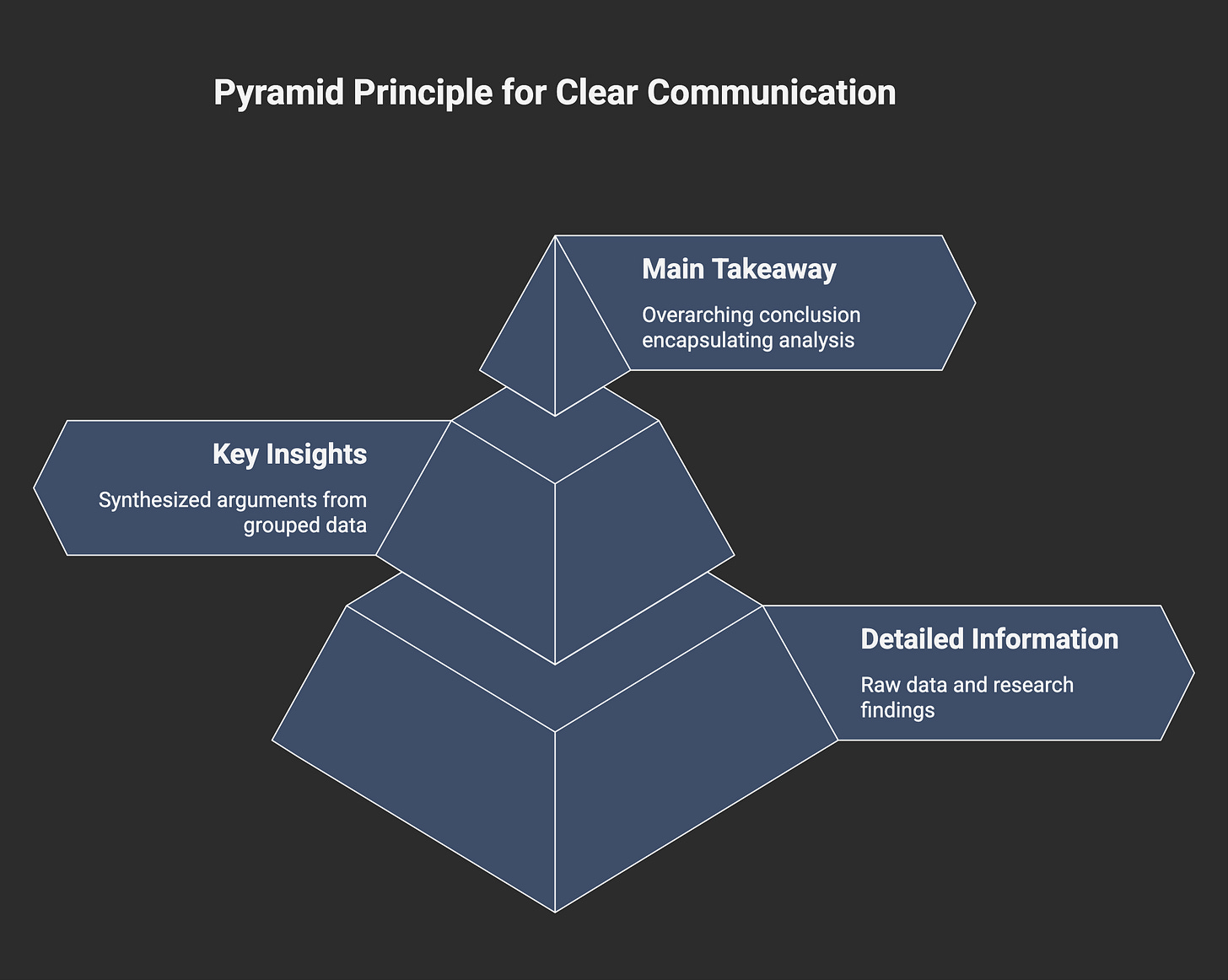

Visually, your ideas form a pyramid with distinct levels:

Lower Level: This base comprises all the detailed information, including data points, survey results, research findings, interview transcripts, and analyses.

Middle Level: These are the synthesized arguments or key takeaways derived from logically grouping and summarizing the information below them. Each point at this level is an abstracted and simplified summary of a cluster of lower-level data.

Highest Level: This is the apex of the pyramid – the single, overarching main takeaway or the core “story” that encapsulates your entire analysis.

The Process of Bottom-Up Synthesis

Building this pyramid is an iterative process of refining thought:

Gather Information: The journey begins with collecting all relevant data. This may involve initial research to verify problem definitions and hypotheses, including surveys, expert interviews, or web research. A helpful tip is maintaining a running document of findings, noting initial takeaways for each piece of information.

Group-Related Information and Eliminating the Irrelevant: As you gather more data, themes emerge. Start grouping related pieces of information. Crucially, a powerful story often comes from eliminating excess information, not just adding more. Though discarding data you’ve spent time compiling can be hard, this distillation is vital for clarity.

Synthesize Groups into Key Insights: Once the information is grouped, the next step is to synthesize each group into a clear insight or argument. This insight becomes a point in the middle level of your pyramid. Minto’s second rule is key here: ideas at any level in the pyramid must always be summaries of the ideas grouped below them. You’re looking to move from specific data points (e.g., “Data points about Squirrels”) to an actionable or descriptive summary (e.g., “The Squirrel Population Is Shrinking”).

Ensure Logical Coherence and MECE Structure:

Minto’s Rules for Grouping: Barbara Minto lays out three rules for this bottom-up thinking:

Ideas within each grouping must always be consistent (e.g., all reasons, problems, and recommendations).

Ideas at any level must always summarize the ideas grouped below them.

Ideas in each grouping must always be logically ordered.

Applying MECE: At each level of the pyramid, the ideas presented must be Mutually Exclusive and Collectively Exhaustive (MECE). This means the individual data points supporting a key insight should be distinct and fully cover that insight. For instance, if you’re discussing the reasons for a problem, each should be unique, and together they should cover all possible causes. Similarly, the key insights at the middle level should be distinct from one another and collectively support the main takeaway at the top. This ensures that your argument is comprehensive and leaves no room for ambiguity.

Logical Ordering: Minto emphasizes that information, if logically structured, will typically be organized in one of three ways: determining causes of an effect (e.g., hypotheses to solve a problem), dividing a whole into parts (e.g., services of a consulting group), or classifying like things together (e.g., types of food at a supermarket). Additionally, order can be imposed by time, structure (e.g., an organizational chart), or degree (e.g., ranking initiatives by importance).

Formulate the Main Takeaway: As your key themes and insights solidify, the main takeaway – the single sentence at the top of your pyramid – should emerge. This is the ultimate summary of your entire analysis.

Avoid ‘Intellectually Blank Assertions’: A common pitfall is creating summary points that don’t truly synthesize the information below them, which Minto calls ‘intellectually blank assertions.’ For example, simply stating ‘The company faces labor and sales challenges’ is less impactful than ‘Escalating labor costs and declining sales volume threaten the company’s profitability.’ The summary must articulate the significance of the grouped ideas. Minto argues that until you have this summarized takeaway, you haven’t completed the thinking process. A vital question is: ‘Why have I brought together these particular ideas and no others?’. By providing clear and meaningful summaries, you can ensure that your communication is impactful and leaves a lasting impression.

This bottom-up process is hard work – the essence of the thinking process. Ignoring it means you never quite say what you mean; worse, you never grasp your thinking.

Delivering the Message: Top-Down Communication

Once you have rigorously structured your thinking from the bottom up, the next step is to communicate your argument effectively, which the Pyramid Principle dictates should be done from the top down.

Start with the Answer

The default and most effective way to communicate using the Pyramid Principle is to start with your main takeaway – the “answer” at the apex of your pyramid. Barbara Minto argues that the primary purpose of communication is to “tell people what they don’t know,” beginning with the most fundamental idea, which sparks curiosity. It makes the audience want to learn more.

There are several reasons for this approach:

Audience Memory: People can simultaneously hold a limited amount of information (around four “chunks”) in their working memory. Presenting the main takeaway and key supporting arguments upfront makes it more likely that your audience will retain the core message.

Respect for Audience Time: It lets the audience immediately grasp the main point. They can then choose how deeply to dive into the supporting details.

Clarity and Impact: Starting with a powerful thesis makes your argument more compelling and easier to follow.

Structuring Top-Down Communication

Your communication should generally follow this structure:

State the Main Takeaway: Begin with the single, overarching point from the top of your pyramid.

Present Key Supporting Arguments: Follow with the 2-4 key insights from the middle level of your pyramid that directly support your main takeaway. Each of these should be a clear, concise summary.

Provide Supporting Data and Evidence: For each key argument, be prepared to drill down into the lower-level data and analysis that substantiates it, if your audience requires that level of detail.

Separate Thinking from Presentation: Write Before You PowerPoint

A common practice in environments like McKinsey is to focus on writing out the argument (e.g., in a memo) before creating presentation slides. This forces you to solidify your thinking and structure your narrative logically without being distracted by visual formatting. After synthesizing bottom-up, “flip” the argument and write it down top-down to see how it flows when starting with the main conclusion. This process can often reveal gaps or weaknesses in your thinking that need further refinement.

Adapting to Your Audience: Direct vs. Indirect Storytelling

While starting with the answer is generally preferred, particularly in business writing, there are situations where a more indirect approach may be suitable:

Direct Storytelling (Answer First): Best for most situations, especially with friendly or impatient audiences, high levels of trust, or when discussing big-picture strategies where there’s already some buy-in.

Indirect Storytelling (Build Up to the Answer): This subtler approach can help ease the audience into accepting your final recommendation if you anticipate resistance, or if you’re dealing with hostile audiences, highly analytical personalities, or those who are fascinated by the data journey itself.

Through its dual process of bottom-up synthesis and top-down communication, the Pyramid Principle provides a powerful framework for anyone seeking to think more clearly, solve problems more effectively, and communicate their ideas with greater impact. While mastering it takes practice, the resulting clarity and persuasiveness are worth the effort.

II. SCQA

In the high-stakes world of software product management, where strategic clarity is paramount and misdiagnosed problems can lead to catastrophic failures, the SCQA framework (Situation, Complication, Question, Answer) emerges as a vital tool for success. It’s a disciplined approach, akin to the MECE principle, designed to cut through ambiguity, define problems with precision, and structure the development of actionable hypotheses. This isn’t just an academic exercise; for product leaders navigating the complexities of market dynamics, user needs, and technical constraints, SCQA provides a robust scaffold for rigorous thinking that separates thriving products from those that merely consume resources.

Too often, product teams jump to solutions before deeply understanding the problem. They see a symptom – such as declining user engagement – and immediately brainstorm features. However, treating symptoms without identifying the root cause is often futile and can be harmful, much like a medical diagnosis. The SCQA framework forces a more methodical approach, ensuring that the problem is accurately framed before a single line of code is considered for a new initiative or a significant strategic shift is contemplated. This disciplined problem definition is an objective fundamental, as critical as customer obsession or execution excellence in building resilient and successful software products.

Deconstructing SCQA: A Framework for Product Precision

The SCQA framework guides product managers and strategists through a logical sequence:

Situation (S): This sets the stage. It’s a concise, factual statement about the current affairs – the established context everyone agrees upon.

Product Example: “Our mobile application has consistently maintained a 4.5-star rating and has seen steady 15% year-over-year user growth for the past three years, becoming a recognized leader in the SME productivity space.”

Complication (C): This introduces the disruption, the challenge, or the change that has occurred within the established situation, creating tension and highlighting the problem.

Product Example: “However, over the last two quarters, new user acquisition has flatlined, and churn among users with less than 90 days tenure has increased by 25%, despite no major changes to our core product or pricing.”

Question (Q): Arising directly from the interplay of the Situation and Complication, this is the core question that needs to be answered to resolve the tension. It frames the central problem that the product team must address.

Product Example: “What are the primary drivers behind the recent stagnation in user acquisition and the spike in early-stage churn, and what strategic product interventions can reverse these trends within the next six months?”

Answer (A): This is the proposed solution or hypothesis – a clear, actionable response to the Question. In the initial stages, this might be a high-level hypothesis that subsequent research and experimentation will validate or refute.

Product Example (Initial Hypothesis): “We hypothesize that new competitors with significantly simpler onboarding flows and more focused feature sets are capturing price-sensitive early-stage users, and that by radically streamlining our onboarding and offering a new entry-level tier, we can regain acquisition momentum and reduce early churn.”

This structured approach ensures that problem-solving is grounded in a clear understanding of context and causality, rather than being reactive and symptom-focused.

SCQA in Action: Driving Clarity Across the Product Life Cycle

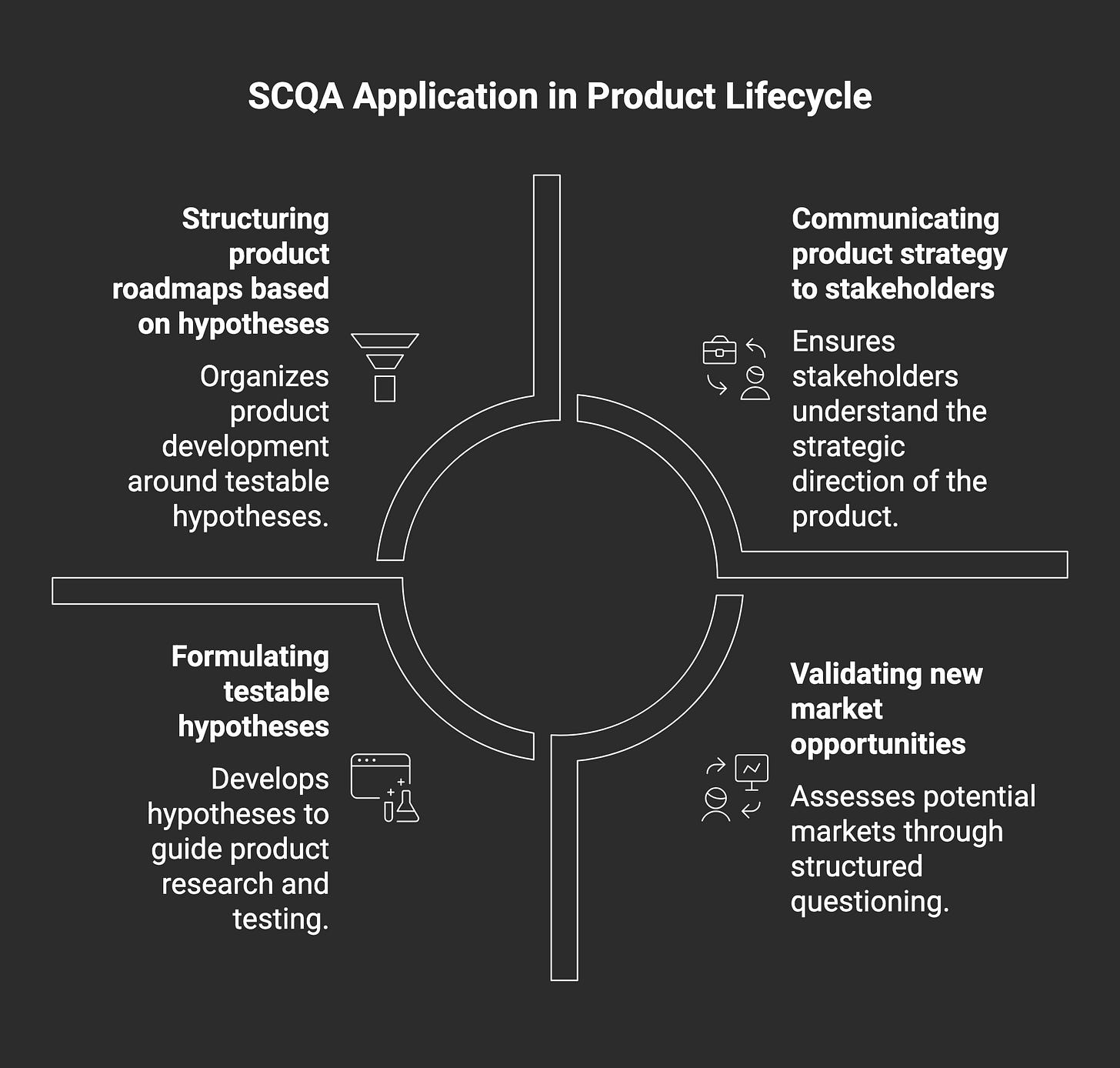

The SCQA framework isn’t just for high-level strategy; its principles can be applied throughout the software product lifecycle, from initial discovery to growth initiatives.

1. Strategic Problem Framing & Product Vision Alignment

Before embarking on major new product initiatives or strategic pivots, SCQA ensures the “why” is crystal clear:

Validating New Opportunities:

S: “Our core B2B product is a market leader in the enterprise segment.”

C: “However, we are observing a rapidly growing SMB market segment with similar underlying needs but a strong resistance to enterprise-level pricing and complexity.”

Q: “Can we adapt our core technology to create a new, simplified offering for the SMB market that is profitable and doesn’t cannibalize our enterprise sales?”

A (Hypothesis): “By creating a feature-limited, self-service SMB version of our product with a distinct branding and pricing model, we can capture significant SMB market share without impacting enterprise revenue.”

Responding to Competitive Threats: When a competitor makes a significant move (as in the ChatGPT example, where competitors emerged quickly), SCQA can frame the response:

S: “Our product ‘Alpha’ has enjoyed a first-mover advantage in the AI-driven analytics.”

C: “A well-funded competitor, ‘Beta,’ has just launched a similar product with aggressive pricing and a feature that directly addresses one of Alpha’s known weaknesses.”

Q: “How can Alpha defend its market share and neutralize Beta’s specific advantage without engaging in a value-destroying price war or derailing our existing strategic roadmap?”

A (Hypothesis): “By rapidly iterating on Alpha’s weak feature and leveraging our existing user base with a loyalty-focused counter-offer, we can mitigate Beta’s impact and solidify our position.”

2. Guiding Product Discovery, Research, and Hypothesis Generation

The “Question” phase of SCQA is where rigorous product discovery and research begin. This is not about finding the answer immediately, but about formulating clear, falsifiable hypotheses that can be tested through user research, data analysis, and experimentation. As the article highlights, a good hypothesis can be disproven.

For the university example provided in the original article (Situation: Successful university; Complication: State budget cuts leading to funding shortfall; Problem: Need to close budget gap), the Question “Can the University cut costs to cover its budget?” leads to sub-questions (hypotheses) like:

“Can the university raise tuition for students to meet costs?” (This could be tested by analyzing price elasticity of demand, competitor tuition rates, and student financial aid capacity.)

“Are other government funding options available?” (Research into grants, alternative public funding streams).

In a software product context, if the Question is “Why is our new feature adoption rate below 10%?”, hypotheses might include:

“Hypothesis 1: The feature’s value proposition is not communicated in the UI.” (Testable via usability studies, A/B testing new messaging).

“Hypothesis 2: The feature is too difficult to discover within the existing navigation.” (Testable via heatmaps, navigation redesign experiments).

“Hypothesis 3: The feature lacks a critical integration required by our target user segment.” (Testable via user interviews, competitor analysis).

These hypotheses, ideally MECE in their coverage of potential root causes, then drive the research backlog and experimental design. This aligns with the principle of execution excellence: iteratively testing assumptions rather than building on unverified beliefs.

3. Structuring Product Roadmaps and Workstreams

Once high-level questions are broken down into testable hypotheses, these can inform the structure of product roadmaps and even how product teams or “workstreams” are organized. As the original article suggests, themes for investigation (e.g., “Tuition & Revenue,” “Government & Financial,” “Cost Cutting & Restructuring”) become logical ways to divide the work. For a software product facing the churn problem mentioned earlier, workstreams might emerge around:

Workstream 1: Onboarding Optimization: Focused on hypotheses related to improving the first 90-day experience.

Workstream 2: Competitive Feature Parity & Differentiation: Focused on hypotheses related to feature gaps or “killer features” of new entrants.

Workstream 3: Pricing & Packaging Innovation: Focused on hypotheses related to entry-level offerings or perceived value for money.

4. Communicating Product Strategy and Decisions

While the original article focuses on SCQA for defining problems and hypotheses, its structure serves as a powerful communication tool, much like the Pyramid Principle it complements. When presenting a product strategy or a proposed solution, structuring the narrative as:

Situation: Here’s where we are / what the market looks like.

Complication: Here’s the challenge or opportunity that has arisen.

Question (Implicit or Explicit): So, what must we do?

Answer/Recommendation: Here’s our proposed product strategy/solution.

This creates a compelling, easy-to-follow narrative that resonates with stakeholders, from engineering teams to executive leadership and investors. It answers the “why” before diving into the “what” and “how.”

SCQA: A Discipline for Objective Product Leadership

Adopting the SCQA framework instills a discipline of clear, logical, and evidence-driven thinking into the very fabric of product management and strategy. It forces product leaders to move beyond assumptions and surface-level symptoms to uncover the true nature of their challenges and opportunities. This is particularly crucial in the African tech ecosystem, for instance, where understanding the nuanced “Situation” and “Complication” of local markets is vital before posing relevant “Questions” and formulating contextually appropriate “Answers” [Why I’m an Angel Investor in Africa].

In a world where adaptability and efficient resource allocation are keys to survival and growth, the SCQA framework is not just a helpful tool; it’s a foundational discipline. It ensures that product teams are always working on the right problems, asking the right questions, and building solutions that have the highest probability of delivering meaningful impact. In the relentless pursuit of product success, the clarity and focus provided by SCQA are indispensable.